英文版:道器合一,施于人生

DAO•QI ~ SPIRIT & VESSEL: SHI YUREN’S STORY

Shi Yuren is its most outstanding representative of Chinese porcelain during the last half of the 20th century. He was the most respected, most knowledgeable artist and teacher in Jingdezhen. His life and work speak not only for porcelain, but for all the artists and intellectuals who triumphed over hardships during China’s last tumultuous century.

Shi Yuren’s story is inextricably bound to the material he so loved; it flows like slip itself down the 1,000 year old river of porcelain history, a river of accumulated wisdom from the past that grows and strengthens as it moves to create new waves ahead. His work featured here and the stories of his life’s journey told by family, friends, and students reveal how he brought the dao and the qi together: the maker and the material, theory and practice, artistic creativity and integrity of character.

Born in Yu Yao, Zhejiang Province, on February 2, 1928, Shi Wenling came from a family of small business people. Orphaned by age 9, he was a diligent student with a precocious talent for art. In his hometown, he was drawing on the sidewalk in front of a Roman Catholic Church when a priest took notice of him. The church gave him support in those difficult, lonely years and taught him the religion he would cherish throughout his life.

In high school, he chose the characters yu and ren for his given names. Taken from a Confucian text whose moral means “whatever you do not like, do not to others,” the characters translate directly as “give to others.” The name was prophetic: until his death at age 68 in a bicycle accident, Shi Yuren shared his wisdom with his students and his love of porcelain with his beloved city, Jingdezhen. He was a man passionately, irrevocably dedicated to art and to teaching. Zhong Liansheng, first generation of students, featured in this exhibition, described him in published article as “the bridge between past and present… who has had the very deepest influence on Jingdezhen’s porcelain through his design ideas and the students he trained.” The gifts Shi Yuren gave would change the direction of porcelain in China and revitalize its heritage during his lifetime and into the present century.

After graduating from Hangzhou Fine Arts Academy in 1952, Shi Yuren studied at China’s most prestigious and rigorous Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts where he graduated at the top of his class in 1954. While still a student in his final semester, he visited Jingdezhen, a rather poor, neglected city at the time, yet trailing clouds of glory as the ancient capital of porcelain manufacture. His Beijing teacher, Mei Jianying, brought him and several other students to Jingdezhen with the purpose of creating a ceramic art education program based on the Central Academy model. At that time, the People’s Republic of China was less than five years old and full of optimism about rebuilding the moribund porcelain industry.

Asked by his teachers to stay an extra year in Beijing, Shi Yuren arrived in Jingdezhen in the spring of 1955, age 27. So young, so knowledgeable, so full of energy and grace, he was thrilled to come to Jingdezhen to teach in the very birthplace of porcelain and especially of qinghua , the brilliant cobalt blue patterns painted under the pure transparent glaze. His strong Zhejiang accent caused a few communication frustrations at first, which his scholarship and friendly personality helped overcome.

During those first years in Jingdezhen, Shi Yuren restructured the curriculum along the lines of the Central Academy. In 1957, there were 73 students at what was then called Jingdezhen Ceramics Technical College; among them were 12 studying wucai (polychrome), 21 studying fencai (powder-based, pastel colors) and 22 studying qinghua (underglaze blue-and-white.) In addition, there were 18 sculpture students. From the outset, Shi Yuren’s outgoing, non-confrontational personality united disparate groups that had been at odds up till then. The famous folk artist, Wang Xiliang, now in his 80’s, speaks warmly about Shi Yuren’s ability to build bridges and reconcile factions. In an interview on November 4, 2003, he also remembers the “deep impression that Shi Yuren’s passion for porcelain” made on him personally and on other folk artists like him who had previously been quite set apart from the “Literati” or academically-trained artists.

Shi Yuren was a founding member of the newly-formed Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute, created in 1958 by merging three schools. He became the first chair of the Ceramic Institute’s Department of Art and Design. His classmate at the Central Academy and a renowned ceramic sculptor in China today, Zhang Shouzhi, remained in Beijing.

The river of Jingdezhen’s ceramic history extends over the millennia as testified to by shards excavated from surrounding kiln sites. The most distinctive achievement of this city and its environs along the Chang River, a tributary of the Yangtze, is the creation of porcelain, a clay body made of feldspathic china stone and kaolin. The mixture is then vitrified by high-firing to achieve its legendary pure whiteness, translucency, ref1ectivity, and resonance. Abundant resources of china stone, kaolin from nearby mountains, timber for kiln fuel, waterways to power the pulverizing trip-hammers and to transport wares, and an industrious labor force guaranteed Jingdezhen’s position at the heart of porcelain.

Jingdezhen is the only city in the world where nearly everyone who lives there has been -- and still is --involved in the process of making, shaping, glazing, painting, packing, selling, and exporting just one commodity. Porcelain in all its manifestations, for decorative display and gifts, everyday use, and industrial purposes, defines the very soul of Jingdezhen, whose original name, Xinping, dates from the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD25-220).Except for a handful of calamities during the past centuries, the production of porcelain has absorbed nearly the entire population of Jingdezhen, even to the present day.

The success of the porcelain enterprise has had its ups and downs corresponding to the political, economic, and social vicissitudes in the country as a whole. Shi Yuren thought often about ways to renew the vitality of Jingdezhen legacy, which had declined since the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, especially since the Japanese invasion in the latter part of the 1930’s. In an article written in the late 1980’s, he wrote about how the porcelain heritage must be made useful for today’s market. He said we should study not only art, but also economics and social relationships, in order to adapt porcelain to contemporary needs. He exhorted the entire community to work together to restore the reputation of Jingdezhen as porcelain’s center. “Jingdezhen is the porcelain city,” he wrote, “so whoever works here has a responsibility to make porcelain flourish.”

Porcelain is not just a material, a shape, vessel, a set of dishes. It engages in a dialogue with the brush to complement the vessel’s three dimensionality. It offers a multi-sensory experience; the eye, the hand, the ear -- all help to convey its aesthetic meaning. In China, the first brush was the brush for calligraphy, an art that worships perfection, requires extraordinary practice and attention, and does not permit correction such as going back to rectify a warped stroke or to fill in an incomplete line. The brush that Shi Yuren held in his hand had been dipped in the 5,000-year old ink of the ancestors. Peng Jingqiang, one of first generation of students, said, “Shi Yuren was the first to bring the spirit of shufa (calligraphy) into the taoci (porcelain).” He gave new energy to the relationship of line and space on the curving surface of the vessel. That freehand, cursive line of the running style is an animated, vigorous stroke mastered by a lifetime of practice and liberated in a transcendent moment somewhat akin to rapture. Zhang Xuewen, another artist among first generation of students, reemphasizes Shi Yuren’s contribution: “My teacher absorbed ideas from the colorful Chinese folk art tradition; he uses color accents, line, and primary subject -- all joined together to form a new style that features fresh rhythms and original decorative compositions.”

Ideally, a porcelain vessel should, like sculpture, be viewed in the round. Its three dimensionality invites us to move through space and time as we “read” its aesthetic narrative. From each viewpoint in space, at each moment in time, we perceive something new. In the finest work, every angle reveals a perfect painting, one after another as we circumnavigate the vessel, and then again as we live with the piece and respond ever more deeply to it over time.

In China, porcelain decorative art has the power of great poetry to teach us about the natural world as well as about the culture. In an article that emphasizes these inter-connections, Shi Yuren wrote, “All art should be true, kind, and beautiful. Reach for perfection to inspire our spirit. Porcelain can satisfy our spiritual needs as well as directly serve our daily needs.” He emphasized the necessity of aesthetics when he wrote about the importance of improving the design of everyday porcelain, even of more humble pieces like sugar jars or rice bowls. Porcelain,he asserted,brings happiness. It lifts the spirits and can cheer us up,no matter what our station society. Although line,color,shape,use,and content may vary,the conventions of aesthetics must not be subverted. If a feeling of aesthetic pleasure,perhaps even ecstasy,is not communicated,then the heritage of porcelain will be squandered,and the intense fire of the dragon kiln will have roared in vain.

Shi Yuren derived techniques and knowledge from each step in its evolution. His preference was for the Ming doucai, called contrasting, joined, or interlocking colors, for the lively energy they emit when juxtaposed. doucai typically involves underglaze outline drawing in qinghua directly on the unfired surface, followed by glazing and high-firing, then filling between the lines with overglaze colors, and finally, refiring at a lower temperature. Shi Yuren’s favorite palette came from .what’s called wucai, which refers, not just to 5 or 8 colors, but to all the polychrome enamels available at any given time. In the 18th century, fencai, also called famille rose, i.e., softer, pastel colors from abroad, expanded the color range further. Shi Yuren was a master of qinghua, youlihong (underglaze red), and what is now called gucai or antique, classical colors. These bright, high-contrast colors sparkle vividly on the vessel, give off an energetic feeling, and delight the eye. During his long career, Shi Yuren himself added to the lexicon by mixing new colors, applying color in unorthodox ways such as incompletely filling the doucai frame, and subtly softening the colors to make them less jumpy. Inspired by aspects from China’s entire porcelain past, he particularly loved the heyday of the early Qing when Jingdezhen experienced a renaissance during the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong periods from 1662 to 1795.

Although porcelain manufacture continued in Jingdezhen despite the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the years of the Republic of China were turbulent when, once again, the country’s trauma was mirrored in the arts. In the first decades after 191l, imitation of earlier Qing wares was common. Although the brushwork might be skilled, the copied motifs and decals quickly became clichés. In Jingdezhen, a group of folk artists produced original word, neither copies nor decals form painting on paper transferred onto the porcelain. Known as the Zhushan ba you, or Eight Friends of the Pearl Mountain, this group met at the full moon to exchange ideas and plan displays. In actuality, more than eight members belonged to the group,which became the bridge between the late Qing and Shi Yuren and his circle.

The Eight Friends sometimes signed their name or applied their seal on the base or body of the finished piece, an uncommon practice before then. After 1911, (with one brief exception in 1915-16) there was no longer any emperor with a nianhao although reign marks were freely used on reproductions. During the first part of the People’s Republic of China, founded in 1949, for the artist to sing his or her name was forbidden. Even today, folk artist s and craftspeople do not usually sign their work.

In old China, traditional knowledge is passed from parent to child, from master to apprentice. Typically in a country where the family -- whose ancestry can be traced in writing for centuries -- is more important than any individual member, the practice of signing the painter’s name on the vessel was atypical. In addition, every piece of porcelain is touched by many hands through but the more than 70 steps required to complete each work. Porcelain requires collaboration from the entire community. This highly-specialized, labor-intensive process begins with the hammer that breaks the china stone and ends with the brush where the painter, atop the pagoda, fulfills the work.

In the folk art tradition, moreover, sometimes one painter applied only one color or did only the calligraphy or just drew outlines or borders -- and did that one thing for life. The notion, therefore, of one person responsible for each vessel in a culture where the community is more important than any single member is not applicable. The western idea of the studio potter -- the single artist who chooses, kneads, throws, glazes, and fires the clay -- does not describe the traditional porcelain process in China.

Shi Yuren wrote an article about the Eight Friends wherein he praised them for helping maintain the porcelain tradition. He described how they struggled hard to be innovative, but much of their work copied Qing painting, especially rice paper painting. Porcelain, however, requires not only its own language, but also its distinctive techniques: even a 2-dimensional plaque made of porcelain cannot simply be painted on as if it were paper. Porcelain is not the same as paper, and the technical skills each requires are not interchangeable.

The book entitled Color Theory of Porcelain Glazes, published in 1961, systematically analyzed, for the first time, all the steps in the process for 20th century artists. Written almost entirely by Shi Yuren, this book did not credit his authorship because of his political problems. Many years later, in Beijing, the chair of the Central Academy of Fine Arts told Shi Yuren that his theoretical writings were still relevant. “Your book is still very useful, even today, which is quite remarkable. When you drew with the stylus, character by character on the waxed paper, you worked so hard to pass this vital knowledge on to your fs.” Typically modest, Shi Yuren nonetheless felt vindicated. In truth, he was among the very first to write about porcelain theory in a systematic way. He made the details of the entire process clear for the first time. All the generations of students he taught would benefit from his scholarly work about design, technique, and color theory.

Unlike most Jingdezhen porcelain artists, Shi Yuren could handle all the steps of the process. He knew the properties of the material and taught these directly in classes. He could throw and supervise f1ring, and he knew all of the decorative art styles from qinghua to gucai to newer, imported enamels. He also knew the nianhao and could date a shard by assessing its composition and decoration. Everywhere he went, he walked or rode his bicycle so as not to miss the chance to find an interesting, old fragment of qinghua. Once, when a new construction job was underway, he stayed up all night to gather shards for his huge collection.

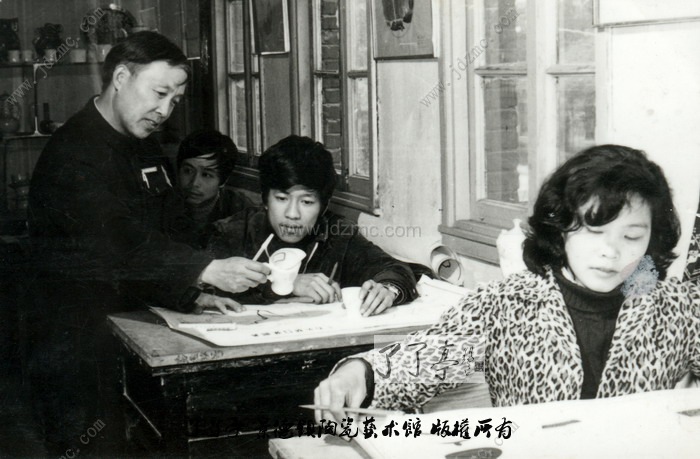

In his teaching, Shi Yuren always stressed the importance of a good foundation. So thorough, so detailed is this foundation that his students included in this exhibition said they feel they always carry it in their subconscious. They say they can still hear their beloved teacher’s voice giving lectures about its fundamental details. Shi Yuren also opened the door to western ideas in art. His Hangzhou and Beijing training gave him knowledge of perspective, chiaroscuro, and the brushwork and color planes of 19th century Impressionism. Such ideas could refresh, but never replace, the tradition.

What are the basic tenets of Shi Yuren’s teaching? First of all, Shi Yuren emphasized the study of the porcelain heritage. This legacy has much to teach at every stage in its development. Know where you have come from in order to help you know where you are going. If you do not have a good understanding of porcelain decorative arts, he insisted, you cannot even imitate well. An academic artist must understand the whole field of porcelain in order to be able to create. Study the pass; be thoroughly familiar with it. Choose what is good from it, discard what is not, and create anew. Be bold in your artistry. Keep hold of the tradition, but search for your own expressive language as you work toward fulfilling your creative potential. He advised students who felt stuck to try something new as opposed to doing the same thing over and over. Keep experimenting; take risks. Since the fire always gives unexpected gifts and the glaze brings surprises beyond the artist’s control, be unafraid to bring your spirit of creativity into the process.

Tradition, however, is a dry husk if not renewed by new ideas or unchallenged by taking risks. Today’s artist must not just copy with a stiff, lifeless brush. Shi Yuren encouraged his students to understand today’s culture and economy in order to make porcelain relevant to contemporary expectations.

In an article written about Shi Yuren in 1987, the artist Zhang Daoyi wrote that Shi Yuren’s works reveal how he “borrows from tradition and fuses it with new content and meaning. He always keeps to the dao (the way), but brings contemporary, new ideas to it.” Shi Yuren echoed this idea about building on the heritage while looking ahead “porcelain arts have many flowers, but there are more f1owers waiting to bloom.”

Next, always be a student of nature, our first and best teacher. Art and life are inseparable. Do not just copy page after page of bamboo leaves, birds, or lotus f1owers, Go outside and look closely with your own eyes. Engaging deeply with the real world will never disappoint. Its inherent life will bring vitality into your art.

Inside the classroom, Shi Yuren was an exacting teacher with a high standard of perfection. Work carefully, work slowly, be precise. Walk outside of the classroom with the same attentiveness. Be familiar with the infinite life out there. Guo Wenlian, one of first generation of students, and his wife, Shu Huijuan, herself an artist and student of Shi Yuren, remember walking in the woods with their teacher. He knew all flowers, insects, and birds as well as the medicinal value of plants. Everywhere he walked, he took cuttings to propagate in his own garden. “If you do not understand the nature of flowers and grass,” Shi Yuren wrote, “how can you make a good design?” you will not be able to make even a good decal or a copy if you do not have an intrinsic knowledge of nature drawn from direct observation of the natural world.

Finally, and most important, Shi Yuren brought together the folk art and the academic art traditions. In the past, there had been a separation between academic artists or the “literati” and the folk artists who learned as apprentices. It was as if the first group spoke a high-brow, formal language and the latter spoke the vernacular. By bridging this divide, Shi Yuren brought about “a design explosion” in Jingdezhen.

In another analogy, it was as if Shi Yuren found equal merit in the official, imperial kilns (guanyao, wherein 99 out of 100 pieces were sometimes destroyed as unfit for the aristocracy) and the civilian, family-operated kilns (minyao). Zhang Xuewen wrote that Shi Yuren’s “greatest contribution is that single-handedly, he boldly combined craft techniques with decorative theory to create a new method and a new porcelain language that recover the true spirit of the porcelain decorative arts.” Shi Yuren’s recognition of the folk arts as the deep and profound source of China’s tradition is perhaps the greatest, most influential gift he gave back to others.

Shi Yuren admired the fresh, direct, free-spirited qualities of China’s folk tradition. He was not a man to make hierarchies of worth; arrogance was not in his vocabulary. A student in Beijing in 1952, just 24 years old, he had no pocket money, so he made a little extra for travel expenses by writing a book about paper cuts, an old folk art practiced usually in the countryside and usually by women. Shi Yuren appreciated the ethnic designs and the interplay of delicate and thick lines made by scissors that cut space out of the ground and leave an unbroken line. Astonishingly dexterous with his hands and eternally democratic in his thinking, he admired many other folk-based crafts such as batik, embroidery, mask painting, and weaving.

For Shi Yuren, the many folk artists living in Jingdezhen were not unschooled artisans; rather, they were “living textbooks,” as artist Yu Jinbao remembers in an August 2002 interview. Shi Yuren talked easily with these folk artists, invited them into his classroom, and occasionally persuaded the Ceramic Institute to hire them as faculty. He took notes from their talks which he then printed out and distributed to his students. Many folk artists such as Duan Maofa, Ye Xingsun, Liu Hanxing, and Wei Min came to his classes to teach. Shi Yuren was especially close to Duan Maofa, who died in 1976. Students recall fondly that when they saw Shi Laoshi carrying tea and a bamboo chair they knew that Duan Maofa had come to teach. Shi Yuren’s connection of the literati with the folk tradition is somewhat analogous to bringing the dao into the qi: the interplay of both forces gives new energy, ideas, and techniques that propel the river of porcelain history forward.

Shi Yuren was not a prolific artist. His teaching took up too much of his time, and he died before he had the chance to enjoy an unencumbered stretch of years for his own work. What are some of the features that tell us his hand touched the vessel? The beauty of his design and color immediately makes itself apparent. He was a perfectionist in all that he did, both as an artist and teacher. His early work is distinctively vivid, original, and bold. “Hang a Shi Yuren plate on a wall,” said Zhang Daoyi, “and it transforms the whole wall. It makes the wall glow with the expression of the Chinese character and spirit.”

In the early 1980’s, Shi Yuren began to create what could be called his signature style. Just when this mature phase began cannot be specified. Nor can the threshold point, the breakthrough moment, be known. Perhaps the folk traditions of textiles gave him a new perspective. Shi Yuren knew how to sew children’s clothing, which meant the handling of fabric, was yet another skill he could do adroitly. Perhaps the undulating movement of Japanese ceramics or quilted patterns inspired him. Would that he were here to tell us. It is sufficient to say that his design transformed the art of porcelain. It added a vocabulary that many, many artists have since appropriated and then used in new ways.

At the same time, Shi Yuren began to examine the potential of the surface to carry new ideas and rhythms. His method now seemed more like quilting or collage, both of which were radically different ways of handling pattern. It was as if he cut out pieces from textiles, qinghua vessels, paper and wood cuts, and other folk crafts and then layered them carefully, onto the skin of the vessel. He placed one piece against another. Always, he understood the 3-D fullness of the curved planes, so the motifs stretched and moved to accommodate the differences made by swelling and tapering.

His process looks almost as if he had taken his treasured shard collection and reglued the pieces -- not to put them back the way they were, but rather, to create a whole new space for something beautiful and lasting. These “quotations” from the past bring the work eternally into the present. His design holds the vessel together with words from long ago, spoken in a voice from today. For the first time, his collage technique breaks up the vessel’s geometry and symmetry, while at the same time, opens up new ways of thinking about how to bring the dao into the qi.

In yet another departure, by wrapping the vessel on the diagonal, Shi Yuren also rethinks porcelain’s traditional verticality. He did what he expected his students to do: learn from the past, find your own voice, and boldly contribute to enrich the heritage of porcelain for the future. Another one of his very special touches was to sprinkle bright red triangles about the vessel, sometimes up and over the lip to the inside. His family says that these colorful geometric forms represent the pieces of red paper left over after fire crackers have gone off. Pop, pop! Pao, pao! You can feel the energy that each touch of red releases. Each triangle speaks of optimism and celebration.

Those bursts of joy came at a heavy price. In 1957, just two years after coming to Jingdezhen with a bounce in his step and hope in his heart, Shi Yuren was 1abeled a youpai or rightist. The only one at the time from his department to be so accused, Shi Yuren was caught first and hit the hardest. No explanation of why he was forced to wear the symbolic maozi or hat of a rightist is credible. No one could truly believe he was an enemy of the country. His colleague and friend, Zhang Zhi’ an, wrote about the tragic repercussions that followed Mao Zedong’s “100 flowers movement” with its subsequent crack-down on intellectuals accused of dissidence toward the fledgling government. In his obituary for Shi Yuren, Zhang Zhi’an wrote, “At first, our hearts were full of sunshine…. We were so naive…. Who could have predicted the storm would come so soon?” Zhang Zhi’an was himself later persecuted after speaking out on behalf of his friend.

In love with porcelain but indifferent to politics, Shi Yuren, this humble, guileless, straight-forward, plainspoken man, had none of that savvy that enabled others to escape entrapment by saying nothing. He knew how to be neither a revolutionary nor a sycophant. His naivete and unsuspecting trustfulness may have doomed him during a time when just one seemingly inconsequential word, twisted or taken out of context by ideologues, could bring disaster. Perhaps, too, Shi Yuren’s Catholic faith made him a scapegoat during those years when the young People’s Republic was trying to be self-sufficient by rejecting anything foreign.

The maozi was a heavy hat for Shi Yuren to wear. At first, he was denied access to the classroom, even denied permission to speak; instead, he was sent to the campus vegetable gardens to work. Soon he became exhausted beyond measure by all-night struggle sessions and all-day hard labor. He was forced to wear a white armband that said, “Youpai Shi Yuren” He and his wife, Liu Haixian, were banished from their home to a damp, tiny farm worker’s barracks with a dirt floor and clay walls. During the period after 1957, any so-called “against-the-government” rightist was shunned. Anyone seen abetting such a person was likely to be snared as well

In those desperate years, no one was allowed to call Shi Yuren “teacher”; to utter the words “Shi Laoshi” was treasonable. The Chinese tradition grants much respect to the teacher, but suddenly, this tradition was overturned. In his poignant memoir about Shi Yuren, Zhang Yuxian, one of first generation of students, remembers how impossible it was to imagine that this gentle, scholarly man could ever be considered unworthy of respect. Once, seeing Shi Yuren return barefoot from the garden with a hoe on his back, Zhang Yuxian wrote, “My heart is heavy. I worry that his loneliness will make him feel desperate, hopeless, in despair. I pray this can pass. When no one was near, I whispered, “Shi Laoshi, take care…” I could tell that he felt comforted. “Eventually Shi Yuren was able to return to the classroom, although for several years, he was not permitted to stand on the podium. At first, too, he had to conduct classes under cover of darkness. Later, he resumed teaching advanced classes and graduate students because he was the only faculty member qualified to do so.

Some time in 1962 or thereabouts, the maozi label was softened. The situation improved marginally for Shi Yuren and Liu Haixian, who now had their first son, Shi Guo, born in her hometown of Tangshan, Hebei Province, in 196l. That was an especially hard year for Shi Yuren and for China, too, when famine raged throughout the countryside. It was terribly difficult to be an artist when everyone was hungry. One student recalls cooking a pumpkin in the wash basin in 1962: two people per pumpkin.

In 1965, on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, Shi Yuren was again targeted. Not much more in the way of material comforts could be taken from him. His salary had initially been 64.05 RMB per month (nearly US $8 at today’s rates, but not equivalent to today’s value). It was lowered to 40 RMB when he was labeled a youpai, and in a national readjustment of wages in 1963, it was raised to 47 RMB where it remained unchanged for the next 19 years. In the hysteria of the Cultural Revolution, his house was nonetheless ransacked. His art -- his brush, his brush holder, his porcelain -- and his classroom, these were once again denied him. For an artist and teacher, that comes far too close to dying.

Nearly every artist and intellectual suffered during the 10 years from 1966-76. Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute was closed for several years, and the campus dormitories housed Changhe auto mobile factory workers. Shi Yuren was assigned to a woodworking factory to make furniture. Even there, he excelled since he was the only one who could interpret the blueprints. His high standards meant that his furniture designs also had to be of superior caliber.

Shi Yuren endured those harsh years because he felt it was the government, not his colleagues or students, who were responsible for the retaliatory behavior. He also knew in his heart that the brutality and marginalization he experienced did not represent the real China. Most of all, he survived thanks to the loyalty and perseverance of his wife, Liu Haixian. In 1958, Liu Haixian, an art student at the Ceramic Institute, married Shi Yuren, even after he had been labeled a rightist. It was a brave gesture, of which her family disapproved. Her decision would require heroic sacrifices throughout her life. She had to give up her own artistic dreams in order to keep alive her husband and family that now included a second son, Shi Di, born in 1966.

Dark times. Shattered lives. So many stories. So much pain. But that is the past. Nevertheless, we cannot help but grieve that Shi Yuren’s curriculum vitae is so short. The story of his professional life takes up just one page because the space between l958 and 1979 is empty.

At one point during the Cultural Revolution, Duan Maofa, Shi Yuren’s teacher and friend, gave him two pieces of porcelain and hundreds of designs. This work was both a gift to help Shi Yuren get back into art from which he had been distanced for so long and a way to guarantee the precious work’s safekeeping. When the hong wei bin (Red Guards) came not long after to Shi Yuren’s house, they burned the papers and smashed the porcelain. Anguished at the loss of his teacher’s work and feeling desperately guilty that he could not protect the designs, Shi Yuren swept up the shards of a small, delicate bowl and glued them back together. He said at that moment, “.It is worth my life to hold on to even one piece of my teacher’s work.” His gesture of preservation is both a living testimony to loss and recovery and a symbol of Jingdezhen’s recent porcelain history.

After Mao’s death in 1976 and the removal of the so-called Gang of Four, the political storm abated. Deng Xiaoping’s appointment as head of state meant that most of the intellectuals and artists were officially exonerated. Shi Yuren also petitioned for and received notice of the erasure of his alleged guilt which finally restored his good name in 1979.

In 1978, Zhu Danian, a well-known artist in Beijing who died in 1995, invited Shi Yuren, his youpai status notwithstanding, to gather a group of Jingdezhen artisans together to create a large mural for the Beijing airport. Shi Yuren and other artists who worked on the design were in truth some of China’s living national treasures. Liu Haixian has carefully preserved Shi Yuren’s original blueprint. Made of elaborately painted porcelain tiles featuring the lush tropical landscape of Yunnan Province, the beautiful mural is entitled “Song of the Forest.” It can still be admired in the airport today.

Thereafter, the blank spaces in Shi Yuren’s resume start to fill in again. His first graduate student was Zhu Legeng, an important porcelain artist now working in Beijing. In 1986, Shi Yuren went to Hong Kong as a participant in the first Jingdezhen ceramic artists’ exhibition. In 1990 to Macao, 1991 to Mongolia, 1992 to Singapore, and 1993 to Korea. He judged exhibitions, lectured, displayed and sold his work as one of Jingdezhen’s master artists, and taught without constraints. Shi Yuren was only 68 years old, in excellent health and revived spirits, when he died instantly on the night of March 3, 1996 after a taxi sideswiped his bicycle. Although a skilled rider, perhaps he could not hear the taxi’s motor on account of an old injury to his right ear sustained during the brutal months of criticism and interrogation. His candle had burned out much too quickly -- and not by nature’s hand. His death left yet more empty spaces, this time in porcelain, in the heart of his widow and family, in Jingdezhen, in China.

This introduction has told a very short version of the life of an extraordinary artist and teacher, who is inseparable from Shi Yuren, the man. To learn more about his character, we need only ask his students, his friends his family. They can tell us about his open-hearted, generous disposition. His tolerance, grace humility, simplicity, and optimism.

In China,the most respected artist should be a model of integrity with exceptionally high moral standards. Shi Yuren was such a man. Strict in class where he always came well-organized and prepared,he expected nothing less from his students. No chabuduo(almost)or mamahuhu(so-so)would do. Generous with his time, gregarious, so considerate of others, he always had time to encourage and mentor his students. Qi Peicai, another of first generation of students, describes his teacher’s big, strong voice that commanded attention in the classroom. No distractions, no interruptions. An honest, virtuous man, Shi Yuren fulfils the ideal of a master artist and teacher.

Outside of class, during the happier years, Shi Yuren loved to dance, something of which he did little during the hard times. When he first came to Jingdezhen, he choreographed a dance for girls that used porcelain soup spoons and saucers to tap out the rhythm, somewhat like castanets. Even during the dark years, he had an irrepressible sense of humor. He was animated, carefree, playful, and even childlike in his enthusiasms. His students remember an outing when everyone else was completely exhausted -- except for Shi Yuren, who impulsively started doing somersaults and headstands to distract the others and refresh their spirits through laughter. On one of several trips to Yunnan Province, his students remember how he danced through the night. With an elephant foot drum on his back, he learned the folk dance steps so quickly that an old village man from an ethnic minority asked him, “Are you a member of the Wa people like me?”

To better understand Shi Yuren’s character, just asks the lay pastor, Zhang Jianzheng, at his church, and he will tell how Shi Yuren worked tirelessly to raise money to replace a building that had burned down. In fact, Shi Yuren was riding his bicycle to Peng Jingqiang’s home to discuss the firing of a piece made for a church fundraiser when the fatal accident occurred. Today, like a phoenix from the ashes, a beautiful new church has been built and furnished where many Jingdezhen people come to worship.

To learn more, ask his widow, Liu Haixian. She might at first lament that her husband had no head for business: he often gave away his work as a wedding present or in exchange for a trifling service. She also tells how he gave over the garden shed to his parakeets whose innumerable breeding cages hung from all the eaves. Hardly major faults, these. She also describes Shi Yuren as a musical man who could play the piano and the accordion and who loved to sing folk songs. A man who could sew clothing, make elaborate paper cuts, heal ducks, feet, graft roses, cut hair, and speak some Russian, Japanese, and English. A man who made good quality furniture when forbidden to teach and who toiled without bitterness when required to pull a heavy wooden cart loaded with porcelain at the Xiangyong Ceramic Factory. A man who gave his ration of rice to his family and kept only the leaves of the pumpkin for himself.

Shi Yuren was a forgiving man, perhaps thanks to his devout Catholic faith. A man who made the most beautiful and creative art in Jingdezhen. This is a Renaissance man for all four seasons in China. The symbolic f1owers of each -- the peony of spring, the lotus of summer, the chrysanthemum of fall, and the plum blossom of winter -- were among his favorites along with orchids, wisteria, night-blooming cereus, and camellias. He is a man who survived a very hard winter indeed.

“If you want to know about porcelain,” said Qin Xilin, one of first generation of students, “you have only to interview my teacher. His spirit glows more brightly than gold.” His light radiates among the generations of artists trained by him. It illuminates the path of porcelain in Jingdezhen and beyond. His spirit shines in the vessels he made and the students he taught; the dao and the qi together, forever.

The article adapted from Carla Coch’s book “Dao·Qi~Spririt & Vessel Master Artist and Teacher Shi Yuren and Seven Artists Among His First Generation of Students”

- 上一篇:道器合一,施于人生(下)

- 下一篇:恩师施于人引我进入艺术殿堂

会员登录

会员登录